Birds are remarkable creatures, exhibiting a range of adaptations that allow them to thrive in diverse habitats. Among these adaptations, vision plays a crucial role in their survival and behavior. One common question arises: Can birds see at night? The answer varies significantly among species, influenced by their evolutionary adaptations and environmental needs. This article explores how different birds perceive their surroundings in low-light conditions, examining their anatomical features, adaptations for nighttime activity, and the science behind their remarkable vision.

Birds’ Vision: An Overview

Understanding avian vision requires looking at both its significance and the physical structures that facilitate it. Vision is a critical sense for birds, enabling them to find food, avoid predators, and navigate during migration.

Importance of Vision in Birds

Birds rely heavily on their eyesight for several essential functions:

- Survival: Effective vision helps birds spot potential threats and prey. For instance, a hawk’s keen eyesight allows it to detect small animals from great heights.

- Navigation: During migration, many birds use visual cues from the environment, such as landscapes and celestial bodies, to orient themselves.

- Social Interaction: Colorful plumage and displays play vital roles in mating and establishing territory, where visual signals can attract mates or deter rivals.

Overview of Avian Eye Structure

Birds possess unique anatomical features that enhance their visual capabilities. Notably, their eyes are generally larger relative to their body size than those of mammals, which allows for greater light intake.

- Eye Position: Many birds have eyes positioned on the sides of their heads, providing a broad field of view. However, some species, like owls, have front-facing eyes that enhance depth perception.

- Photoreceptors: Birds have two types of photoreceptors in their retinas—rods and cones. Rods are responsible for low-light vision, while cones enable color detection.

| Feature | Birds | Humans |

|---|---|---|

| Eye Size | Larger relative to body | Average for head size |

| Color Vision | Superior (includes UV) | Limited |

| Rods to Cones Ratio | High rods for night vision | Fewer rods |

Anatomy of a Bird’s Eye

To understand how birds see, we must delve into the specific structures that comprise their eyes. Each component contributes to their ability to perceive light and movement effectively.

Eye Size and Structure

Birds typically have relatively large eyes, which allows more light to enter. This is especially important for species that are active at dawn or dusk, where lighting conditions are low.

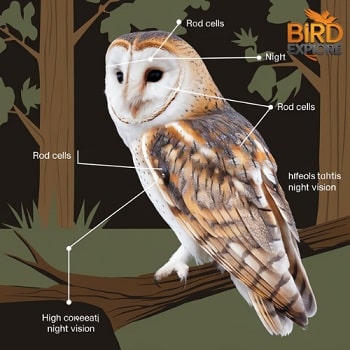

Photoreceptors in Bird Eyes

Birds have an impressive number of photoreceptors compared to humans:

- Rods: These are more sensitive to light and enable vision in dim conditions. Birds have a higher concentration of rod cells, enhancing their ability to see in low light.

- Cones: Responsible for color vision, birds have multiple types of cones, allowing them to see a broader spectrum of colors than humans. Some birds can even see ultraviolet light.

The Role of the Tapetum Lucidum

Many nocturnal birds possess a layer called the tapetum lucidum located behind the retina. This reflective layer bounces light back through the retina, effectively increasing the amount of light available to photoreceptors. This adaptation is crucial for enhancing night vision, allowing these birds to see better in near darkness.

Factors Affecting Avian Night Vision

Several factors influence a bird’s ability to see at night, including species variation, eye structure, and environmental light conditions.

Species-Specific Variations

Not all birds are created equal when it comes to night vision. Nocturnal species have evolved unique adaptations that enable them to excel in low-light environments.

- Owls: Known for their exceptional night vision, owls have large eyes, a high density of rod cells, and a tapetum lucidum. These features make them highly efficient hunters at night.

- Nightjars and Nighthawks: These birds also have large eyes with a high concentration of rods, allowing them to hunt insects during twilight hours.

Conversely, diurnal birds, such as hawks and sparrows, possess adaptations better suited for bright light but are less capable in darkness.

Eye Structure and Configuration

The physical configuration of a bird’s eyes plays a crucial role in its night vision capabilities.

- Eye Shape: Birds with front-facing eyes, such as owls, benefit from binocular vision, allowing them to gauge distances accurately, which is essential for hunting.

- Eye Position: Species with laterally positioned eyes, like pigeons, have a broader field of view, enabling them to spot predators more easily, but they sacrifice some depth perception.

Environmental Light Conditions

The ability to see at night is also influenced by the surrounding light conditions. Factors include:

- Natural Light Sources: Moonlight can significantly enhance visibility for nocturnal birds, while urban areas may introduce artificial lighting that can confuse migratory and night-active birds.

- Behavioral Adaptations: Birds may alter their activity patterns based on the availability of light. For instance, many nocturnal birds become more active around dusk and dawn.

Nighttime Birds: Masters of the Night

Certain birds have adapted exceptionally well to life after dark. These adaptations enhance their hunting and navigation skills, allowing them to thrive in low-light environments.

Owls: The Iconic Night Hunters

Owls are perhaps the most recognized nighttime birds, known for their distinctive features and remarkable hunting abilities.

- Large Eyes: Their large eyes enable them to capture more light, enhancing their ability to see in dim conditions.

- Facial Disc: This unique feature helps funnel sound waves, significantly improving their hearing, which is vital for locating prey in the dark.

- Nocturnal Behavior: Most owls are primarily nocturnal, allowing them to hunt effectively while avoiding daytime predators.

Adaptations for Hunting

Owls have several adaptations that make them expert hunters at night:

- Silent Flight: Their feathers are specially structured to reduce noise during flight, allowing them to approach prey stealthily.

- Keen Hearing: The ability to locate sounds precisely helps them hunt even in complete darkness.

Nightjars and Nighthawks

These birds are also masters of the night, employing unique adaptations for survival.

- High Rod Density: Nightjars and nighthawks have a high concentration of rod cells, allowing them to hunt insects effectively at dusk and dawn.

- Camouflage: Their plumage often mimics the colors and textures of their surroundings, helping them blend into their environment and avoid predators.

Kiwis and Their Unique Vision

Kiwis are unique among birds, exhibiting different adaptations compared to their nocturnal counterparts:

- Limited Vision: Kiwis possess relatively poor eyesight compared to other birds.

- Enhanced Senses: They rely heavily on their exceptional sense of smell and sensitive whisker-like feathers to navigate and find food in the dark.

Diurnal Birds: Daytime Vision and Adaptations

While many birds are active during the day, some diurnal birds possess adaptations that allow them to see relatively well in low-light conditions.

Birds of Prey

Hawks and eagles are prime examples of diurnal predators that rely on sharp vision for hunting. Their adaptations include:

- Excellent Color Vision: They can see a wider spectrum of colors, allowing them to spot prey from great distances.

- Light Sensitivity: Although adapted for bright daylight, they can still see well during twilight hours, enabling effective hunting at dawn and dusk.

Songbirds

Many songbirds are primarily diurnal but may exhibit some activity during low-light conditions. Their adaptations include:

- Dawn Chorus: Many songbirds are most active during the early morning and late evening, taking advantage of lower light levels to avoid predators.

- Flexible Vision: Their eyes are adapted to handle varying light conditions, though not as proficient as those of nocturnal species.

Migratory Birds and Night Navigation

Migratory birds often travel at night, a behavior that helps them avoid daytime predators and reduces exposure to the heat of the sun during long journeys. Their navigation strategies are particularly fascinating.

Celestial Navigation

Many migratory birds use the stars and other celestial bodies for orientation during their nocturnal journeys.

- Star Recognition: Studies have shown that birds can recognize specific constellations and use them to guide their paths.

- Brain Processing: Research suggests that particular brain regions in birds are dedicated to processing celestial information, enhancing their ability to navigate at night.

Magnetic Field Detection

In addition to visual cues, some birds can detect the Earth’s magnetic field, which aids their navigation. This ability is particularly valuable on cloudy nights when stars are obscured.

- Mechanisms of Detection: Specialized cells in the retina are believed to respond to magnetic fields, providing birds with an internal compass for orientation.

Comparative Vision: Birds vs. Humans

To understand avian night vision better, we can compare it to human vision. This comparison highlights the remarkable adaptations that birds possess.

Light Sensitivity

Birds generally have more rod cells than humans, which makes them more sensitive to light. This increased sensitivity allows them to see in much lower light conditions.

Color Vision

Most birds have superior color vision compared to humans, being able to see ultraviolet light that is invisible to us.

| Aspect | Birds | Humans |

|---|---|---|

| Rod Cells | Higher concentration | Fewer |

| Cone Cells | Specialized for color | Limited to visible spectrum |

| Ultraviolet Sensitivity | Present | Absent |

Field of View

Birds typically have a wider field of view due to the placement of their eyes:

- Lateral Eye Position: Many birds have eyes on the sides of their heads, granting them nearly 360-degree vision but sacrificing some depth perception.

- Front-Facing Eyes: Nocturnal birds like owls benefit from forward-facing eyes, which provide excellent depth perception critical for hunting.

Conclusion about Can Birds See at Night?

Birds’ ability to see at night varies greatly among species, shaped by evolutionary adaptations and environmental factors. Nocturnal birds like owls have specialized features, such as large eyes and a high density of rod cells, allowing them to hunt and navigate effectively in low-light conditions. Diurnal birds, while less adept in the dark, still possess notable visual adaptations for varying light conditions.

Migratory birds employ a combination of enhanced vision, celestial navigation, and magnetic field detection to traverse long distances at night. Understanding the diversity in avian vision showcases the remarkable adaptations that allow birds to thrive in their unique environments.

Kay Lovely is a dedicated writer for Bird Explore, where she brings the latest celebrity news and net worth updates to life. With a passion for pop culture and a keen eye for detail, Kay delivers engaging and insightful content that keeps readers informed about their favorite stars. Her extensive knowledge of the entertainment industry and commitment to accuracy make her a trusted voice in celebrity journalism.